Uniquely Brilliant Brush Work

Artist Ha mixes traditional black and white brush work with colors to create magic with subjects filled with humor, satire

Artist Ha Young-sang, with the penname Buekchun, does a marvelous job with his bold initiative of mixing traditional black and white ink brush painting with modern painting by adding color to his inimitable work.

Artist Ha Young-sang, with the penname Buekchun, does a marvelous job with his bold initiative of mixing traditional black and white ink brush painting with modern painting by adding color to his inimitable work.

Ha¡¯s work, based on India ink, which sums up every object with the liberality of unfettered brushstrokes, features brief and implicative temperance and great morale, says art critic Kim Sang-chul in his critique of Ha¡¯s artistry.

¡°The strokes of the brush once made cannot be brought back or modified,¡± he says. This characteristic, especially, becomes more prominent in the base of Ha, who uses delicate Chinese drawing paper, which reacts very sensitively. Ha¡¯s work on the sensitive Chinese drawing paper is the result of the moment, since it records not only the  momentary movement of the strokes of the brush, but also the time of remaining and outstretching.

momentary movement of the strokes of the brush, but also the time of remaining and outstretching.

The core that leads must be unrestrained lines. Ha¡¯s lines reflect instant and impromptu inspiration rather than follow certain rules or laws. They are fast, rough, dull and unfettered rather than the smooth and elegant beauty of curve. Ha expresses and sums up every object by using the straight line rather than smooth and elegant circles. Ha follows the value of angularity. His unique style of drawing, which is made by this way of stroking the brush, is a sort of paradox and deviation.

Although Ha¡¯s screen, which consist of poetry, calligraphy and painting, reminds viewers of a painting in the literary artist¡¯s style, his work does not always devote itself to the fixed pattern of a painting in the literary artist¡¯s style. Kim goes on to note that Ha¡¯s work might be understood as a painting in the style of Zen Buddhism because of its Buddhist subject matters like Dharma and maggots, but it is not enough to define his work in this way. It is true that Ha¡¯s work cross the border of the divineness and the mundane. The coordinates on which Ha¡¯s work is located are to have affection toward the mundane world, but not to be biased, and also, to pursue the border of the divine, yet to guard itself against isolation from reality. Hence, in Ha¡¯s work, the divine and the mundane intersect each other while ideal and reality exist simultaneously.

India ink is not a good tool for the objective reproduction or description. The reason India ink constantly emphasize the expression of one¡¯s ideas is none other than the need for a subjective viewpoint and representation. In other words, India ink demands the manifestation of the implicative meaning through inward eyes, while description or reproduction works demand it through naked eyes.

To understand and appreciate India ink painting is not to look at the shape drawn by India ink, but to notice the inner meaning and content. This is why people say one must read India ink paintings, not look at them. Ha¡¯s screen, which is composed of implication and temperance, is also full of metaphors and symbols. Sometimes, it expresses the peculiar taste of a painting in the literary artist¡¯s style, but sometimes, contains bitter satire on the reality and the order of the world. Ha¡¯s satire is unrestrained since it expresses itself actively, rather than treats things moderately and passively. Especially, his work that features satire and humor using animals allow the viewers to feel the straight thrill through the unfettered expression.

The art critique went on to say that the metaphor within humor and satire is the high-end artistic expression, which is made based on the implication and current tendency. It does not depend on the eyesight, but works on the viewer¡¯s mind. Satire does not suggest specific situation or content directly, but reveals them in a roundabout way. This brings the strong point of satire to enlarge the viewers room for the imagination and interpretation. It allows viewers to give a smile of satisfaction through the implication and metaphor of a pithy remark.

The world of implication that Ha shows does not pursue the preexisting value of a painting in the literary artist¡¯s style such as manner or dignity, but expressed the frank reaction to the space-time that it is involved in. Thus in Ha¡¯s work, there are new and various objects and expressions, rather than fixed materials within a painting in the literary artist¡¯s style.

This must be the reason his rough and crude screen is fresh and interesting. Ha¡¯s screen, which sometimes emphasizes things directly, but sometimes points out the phenomena through implicit metaphor, allows viewers to automatically read Ha¡¯s thoughts and introspections.

The painter not only satirizes too huge and idealized values by using the extremely mundane thing, but also expresses his own feeling about the meaningless mundane value implicatively with the contemplative viewpoint. It is expressed as his own peculiar screen, by dealing with the divine and the mundane at the same time. Although it is unfettered because it is not bound by matters or certain rules, the biggest strong point of Ha¡¯s work must be purity.

This does not mean the mere plastic value that is manifested from functional things, but the specific value which comes from the deep inner side. Bitterest satire or supremely elegant technical skill eventually becomes vulgar if it becomes impure.

Ha¡¯s strokes of the brush have their own nobility despite their roughness and crudeness. Even though his satire is strong and incisive, the satire itself cannot be the only factor that defines the overall nobility of his work. It is true that Ha¡¯s work is composed of unfettered, sharp human satire, but it also contains certain nobility and unique style. The reason for this must be the reflection of the artist¡¯s reality and ideals, which are purified and then expressed on the screen. Ha¡¯s world of humor and satire within the current mountainous waves of modern art, composed of aggressive plasticity and rampant expression is more than the succession of tradition. It is the peculiar thing that can be obtained through the unique interpretation of the tradition. The presence of the painter¡¯s strenuous effort within this reality, the collapse of traditional values caused by the overflowing of Western plasticity, is definitely welcome. nw

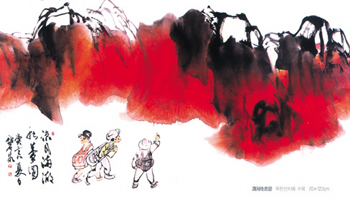

Road with Flowers: 70-x 223 cm; Korea paper.

The Republic of Korea: 65 x 55 cm; Korean paper.

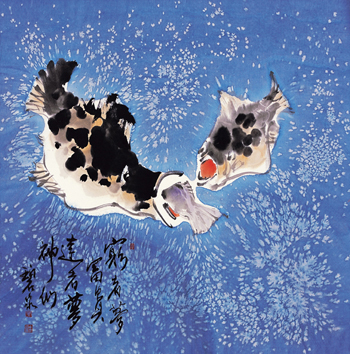

Playing in Dreams: 70 x 68 cm: Korean paper.

Thousand Years Old Cranes: 70 x 137 cm: Korean paper.

A Mountain Scene in Autumn: 70 x 127 cm: Korean paper.

Flute Player: 137 x 70 cm: Korean paper.

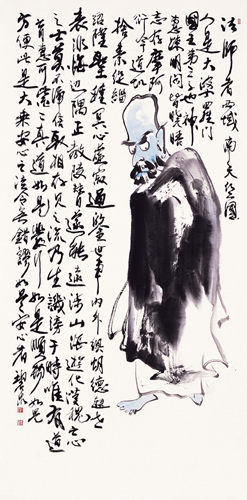

A Dalma Portraiture: 137 x 70 cm: Korean paper.

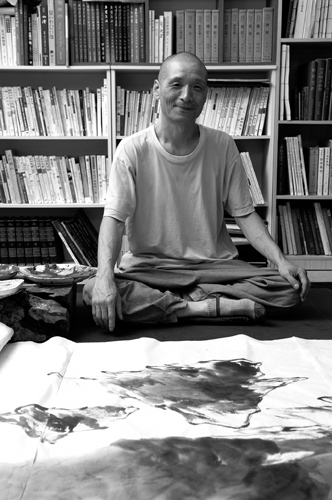

Artist Buekchun Ha Young-sang.

3Fl, 292-47, Shindang 6-dong, Chung-gu, Seoul, Korea 100-456

Tel : 82-2-2235-6114 / Fax : 82-2-2235-0799