Art through Prism of Light

Painter Woo works wonders with light in variety of artistic forms

Among the social changes that ushered in the turbulent period of art, nothing was more shocking than consequences from the scientific revolution of the late 19th century and early 20th century. The invention of airplanes has enabled us to cross the Atlantic in a day instead of a month and thanks to the invention of the internal combustion engine, we live in an era of mass production and consumption. These technological advances have been of such magnitude as to reorder the living patterns of mankind. As regards these changes have led to the discarding of representation which can be achieved with the camera and the adoption of a more subjective method that allows new viewpoints which can better respond to the challenges presented by this new era of possibility. That is to say, the birth of abstract art was necessary to the change of social conditions.

Among the social changes that ushered in the turbulent period of art, nothing was more shocking than consequences from the scientific revolution of the late 19th century and early 20th century. The invention of airplanes has enabled us to cross the Atlantic in a day instead of a month and thanks to the invention of the internal combustion engine, we live in an era of mass production and consumption. These technological advances have been of such magnitude as to reorder the living patterns of mankind. As regards these changes have led to the discarding of representation which can be achieved with the camera and the adoption of a more subjective method that allows new viewpoints which can better respond to the challenges presented by this new era of possibility. That is to say, the birth of abstract art was necessary to the change of social conditions.

The paintings of Woo Jae-gil have had as their subject matter the image of light, and they are not modeled after modernist paintings of the 20th century.

Instead, the straight line painting of geometric patterns and the remarkable contrast of light and darkness manifest the material of light. Woo's work show the distribution and arrangement of light using a prism effect, thus rejecting the perception that the light is a mere energy. The faults of this light, being cut and divided in a sharp manner, express a will to reject eternal compromises.

Instead, the straight line painting of geometric patterns and the remarkable contrast of light and darkness manifest the material of light. Woo's work show the distribution and arrangement of light using a prism effect, thus rejecting the perception that the light is a mere energy. The faults of this light, being cut and divided in a sharp manner, express a will to reject eternal compromises.

It is exciting to view the work that Woo has created over a career that has spanned for 20 years and to associate the relationship between the light and artist.

He would say on his art pieces, "Among the lines, I like the straight line best. The reason for this attraction lies in the fact that the straight line expresses an upright and tenacious character. It seems that I like these lines because of all my innate faults and will to cultivate within myself the character expressed in such lines."Such simple remarks by Woo seem to be related to the artist, the motive for his work, and his attitude towards art than to the spirit of the times,

civilization or the aesthetics of the industrial society. They contain an Oriental aesthetic notion that art is the hidden inner language of an artist than mere description is a small part of the image. However, one cannot say that the curve is compromising, distorted and one-sided. In fact, Woo's etchings are full of intentional curves used to void "simple line-drawing,"and the self-consolation provided by such curves does not contain meaningful changes or prophetic message. He is drawing straight lines in spite of himself and the lines are altered into a messenger that passes the subtle light to somewhere on the other side of the prism.

The strength that allows the artist to endure the monotonous involved in such painstakingly precise work comes no doubt from his inner desire for producing and telling something. Woo's early works, which were done during the 50s and 60s, reminds one of the abstract paintings of Robert de Laune or Kandinsky.

Through these words of his apprenticeship, we can modernize that the artist has a highly developed sense of organization for the meaning of color and light. In his works of the middle and late 60s, one finds abstract dot-painting or colorful line structure in the style of Mondrian.

Through these words of his apprenticeship, we can modernize that the artist has a highly developed sense of organization for the meaning of color and light. In his works of the middle and late 60s, one finds abstract dot-painting or colorful line structure in the style of Mondrian.

As Woo evolves, one begins to recognize the originality that begins to appear in paintings that manifest the reflection of light and the objects to be projected by the light. His straight lines and light are decided by the object that they reflect and concealment and the disclosure of the things that pass.

As a material reflects light, some aspects of it accepts the light and others don't, and the viewer can see only the reflected areas. This idea is shown clearly in the Rhythm series of 1976. These works express the rhythm , of the movement of a whirling ribbon on the head of the leader of a Korean traditional Farmers Band(nongak) but one learns this only through the artist's comments, but from the painting itself.

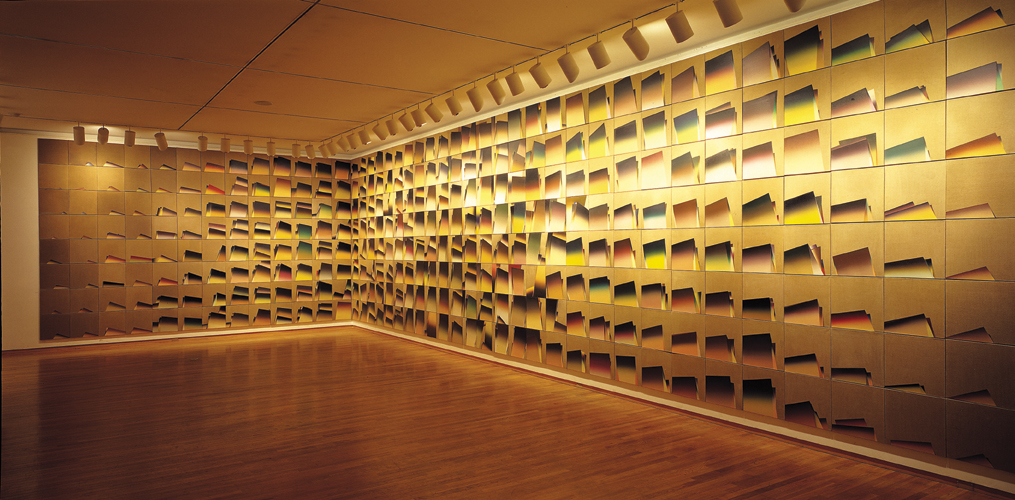

Painter Woo's work displayed many variations since the 1980s. One of the variations is the evoking of the world of the traditional sense of beauty through collages made from traditional paper, Hanji, that is used in old books. This method is not simply borrowed but is rather a subtle adoption of our traditional material and emotion to the techniques of the artist. Through this medium, Woo is able to exclude the smell of mechanism and the cold feeling of oil painting. This kind of variation, which has accepted the free will of the artist rather than the self-regulation of the screen, is much different from the viewpoint of the 1970s. It seems that the painter is now emphasizing his surroundings and his traditions with the intension of fusing tradition and the modernity together.

Painter Woo's work displayed many variations since the 1980s. One of the variations is the evoking of the world of the traditional sense of beauty through collages made from traditional paper, Hanji, that is used in old books. This method is not simply borrowed but is rather a subtle adoption of our traditional material and emotion to the techniques of the artist. Through this medium, Woo is able to exclude the smell of mechanism and the cold feeling of oil painting. This kind of variation, which has accepted the free will of the artist rather than the self-regulation of the screen, is much different from the viewpoint of the 1970s. It seems that the painter is now emphasizing his surroundings and his traditions with the intension of fusing tradition and the modernity together.

Another important variation is the fact that the magnification of the plane has expanded the cubic sense so that the cubic era of the paintings has seen a dramatic increase. His recent works are 11 meters and differentiate the object of paintings from the abstractness and geometricity of the previous ones. 2005.

Now the light doesn't need to conceal but to place in space the object from which it shines, resulting in a color ribbon effect. These color ribbons are only partially depicted and are so subtle that they cannot be easily visualized. However, it is easily recognized that the color of these ribbons is derived from our traditional colored, namely, the saekdong.

The long white ribbon on the head of the leader of our traditional farmers'band, which streams through the space into the universe, evokes a mystical atmosphere. But Woo's work does seek to portray the play of the Farmers Band but rather to capture the shape of the white ribbons and the monetary figure made by it.

Working with Hanji, the traditional Korean paper, is not easy as it involves a lot of work, a complicated work procedure-the arrangement of the paper, the planning of the collage, the transplanting of the calligraphy, and the sensitization and dying. Woo has produced a large number of work this year despite the tough work,

requiring extended time of labor. In addition, the brilliant color, the traditional sense of quality, the speed of forms, were all new to Woo's work.

requiring extended time of labor. In addition, the brilliant color, the traditional sense of quality, the speed of forms, were all new to Woo's work.

Considering the volume it would be safe to say that they were all poured out. In the end, however, Woo returns to the abstract with works which are bolder and more formalized. Woo Jae-gil appears to think that it is high time to say goodbye to the typical language of the abstract period with its dependence on power, speed and space and to replace it with an art that exposes ripe emotions. A retrospective view of his work reminds one of a monodrama, the great part of which is already done. nw

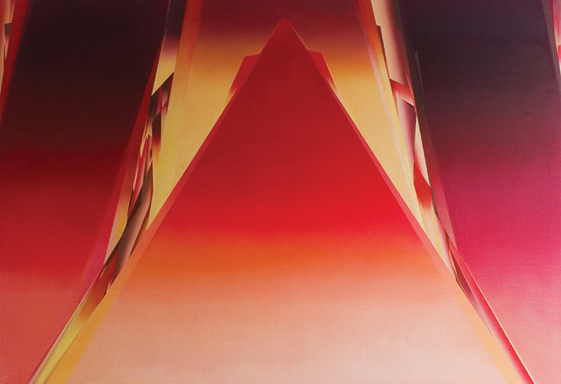

Light | 2006-5H | Oil on canvas | 291.0¡¿197.0§¯

Painter Woo Jae-gil. The Fine Arts Museum operated by by the renowned painter in Gwangju.

Light | 2004 | Self Reflection Mirror | Sainless Steel | 301x285x211§¯

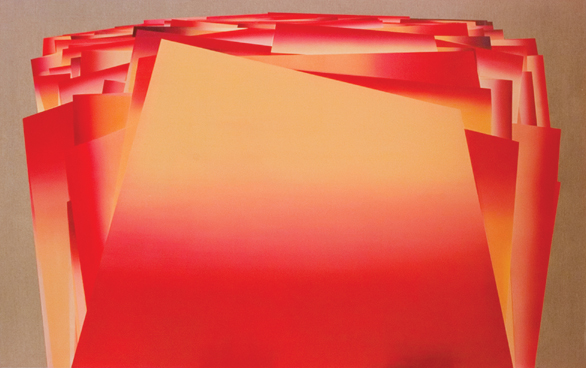

Light | 2006-5A | Oil on canvas | 259.0¡¿162.0§¯

Work | 99-1A | Oil on canvas | 4050.0¡¿1215.0§¯

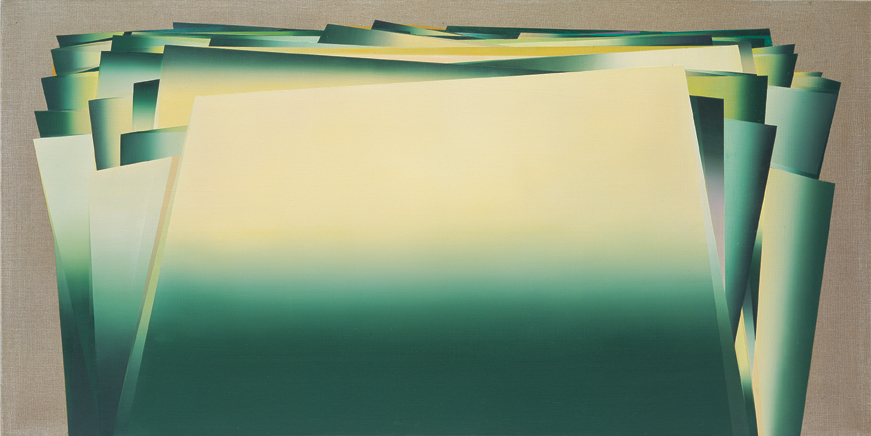

Light | 2006-5D | Oil on canvas | 194.0¡¿97.0§¯

Light | 2003-3D | Stainless Steel | 280¡¿280¡¿325§¯

3Fl, 292-47, Shindang 6-dong, Chung-gu, Seoul, Korea 100-456

Tel : 82-2-2235-6114 / Fax : 82-2-2235-0799